Niederlanden, Nederlandse Reisopera, Premiere L'Orfeo - Monteverdi, 25.01.2020

L'Orfeo - Claudio Monteverdi

Favola in musica, Libretto by Alessandro Striggio, World Premiere: 24 februari 1607, Palazzo Ducale, Mantua

Premiere 25.01.2020

Artistic team

Conductor - Hernán Schvartzman

Concept - Monique Wagemakers, Lonneke Gordijn (Studio DRIFT), Nanine Linning

Director - Monique Wagemakers

Choreographer - Nanine Linning

Installation ‘Ego’ - Lonneke Gordijn (Studio DRIFT)

Costume design - Marlou Breuls

Lighting design - Thomas C. Hase

Cast

La Musica / Messagiera / Proserpina - Luciana Mancini

Orfeo - Samuel Boden

Euridice / Speranza / Eco - Kristen Witmer

Caronte / Spirito - Alex Rosen

Plutone / Pastore / Spirito - Yannis François

Ninfa - Lucía Martín-Cartón

Apollo / Pastore / Spirito - Laurence Kilsby

Pastore / Spirito - Kevin Skelton

Pastore / Spirito - Nils Wanderer

Spirito - Damien Pass

Dancers Dance Company Nanine Linning - Demi-Carlin Aarts, Mirko de Campi, Luca Cappai, Kimmie Cumming, Milan van Ettekoven, Anna Suleyman Harms, Boglarka Heim, Sergio Indiveri, Hang-Ceng Lee, Kyle Patrick

Orchestra - La Sfera Armoniosa

The opera is sung in Italian with Dutch and English surtitels

The performance last 2 hrs and 20 minutes, including one interval.

Termine : Enschede (25 Jan, première), Leeuwarden (31 Jan), Maastricht (2 Feb), Utrecht (7 Feb), Amsterdam (9 + 11 Feb), Rotterdam (13 Feb), Zwolle (15 Feb), Arnhem (20 Feb), Den Haag (22 Feb).

Starting Saturday, 25 January 2020, Nederlandse Reisopera (Dutch National Touring Opera) will tour the Netherlands with a new opera production of L’Orfeo (1607, Claudio Monteverdi). The artistic team of this production has made this first ‘primal opera’ of Monteverdi into a contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk in which the artistic team blend together stage direction, choreography and design into a unique production from the very beginning.

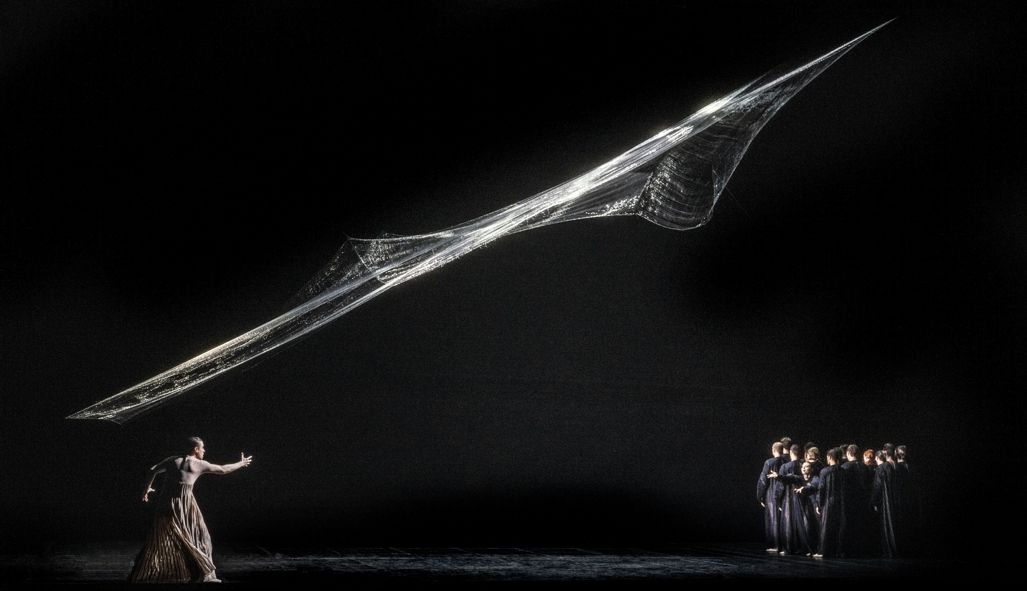

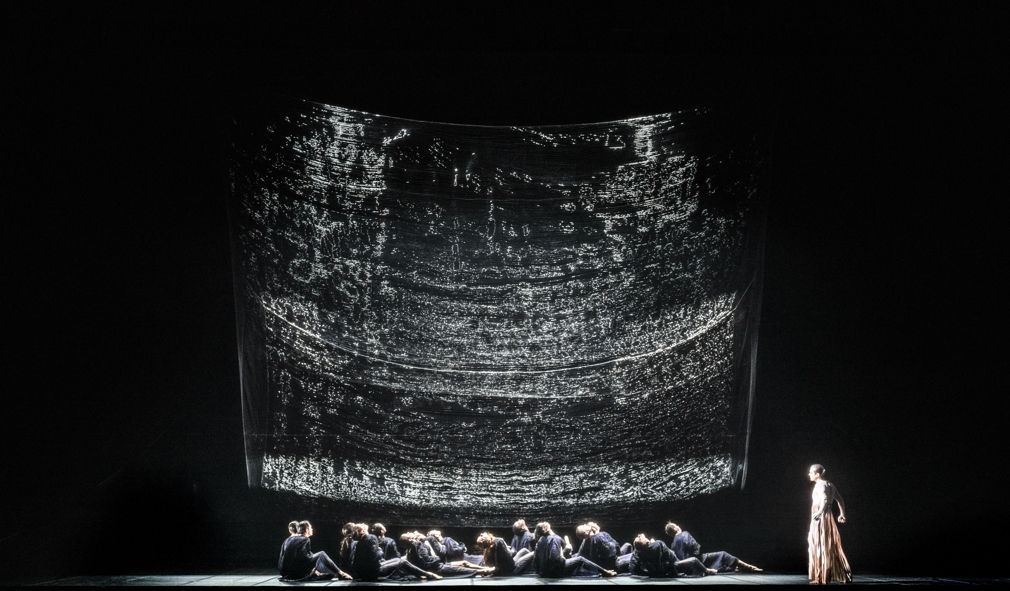

There is no ‘set’ on the stage; instead, we see the moving installation Ego by artist Lonneke Gordijn (Studio DRIFT). The direction/choreography of Monique Wagemakers and Nanine Linning makes no distinction between singing and dancing scenes: the ten singers and ten dancers, together with Ego, form one single organism that retains the audience’s attention during the entire performance. The costumes of fashion designer Marlou Breuls accentuate and enhance the effect of homogeneity. Hernán Schvartzman (OPERA2DAY) is the musical director of this production, conducting the Baroque ensemble La Sfera Armoniosa.

L'Orfeo Monteverdi youtube Trailer Nederlandse Reisopera [ Mit erweitertem Datenschutz eingebettet ]

THE CONCEPT: A CONTEMPORARY GESAMTKUNSTWERKDirector Monique Wagemakers, together with choreographer Nanine Linning and artist Lonneke Gordijn (Studio DRIFT), developed the concept for this opera as a contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk that fully integrates stage direction, choreography and design. Fashion designer Marlou Breuls was brought in to create the costumes. Right from the start, Wagemakers’ intention was to find a new way to make opera. This is why she deliberately sought collaborations with independent artists.

On working with Lonneke Gordijn, Monique Wagemakers says, ‘Lonneke has a fascination for nature; with her installations she operates at the edge between life and death, between day and night, between being frozen in rigidity and getting moving – exactly what Orpheus is about.’ Choreographer Nanine Linning incorporates her strongly personal and physical dance language into this concept. The ten dancers of her Dance Company are part of the cast. Because singers and dancers in this production form a single group and are always onstage, Linning was also involved in the casting of the singers.

THE STORY OF L’ORFEOOn the day Orpheus and Eurydice get married, she is bitten by a snake and dies. Orpheus cannot accept her death. He decides to descend to the underworld, the kingdom of the dead, in a final attempt to retrieve her and thus recover his happiness. He convinces the gods of the underworld to let Eurydice return with him to the kingdom of the living. Pluto gives his permission but forbids Orpheus to look back at Euridice while on the way back to the upper world. Orpheus feels insecure and looks back towards Euridice anyway, losing her for a second time.

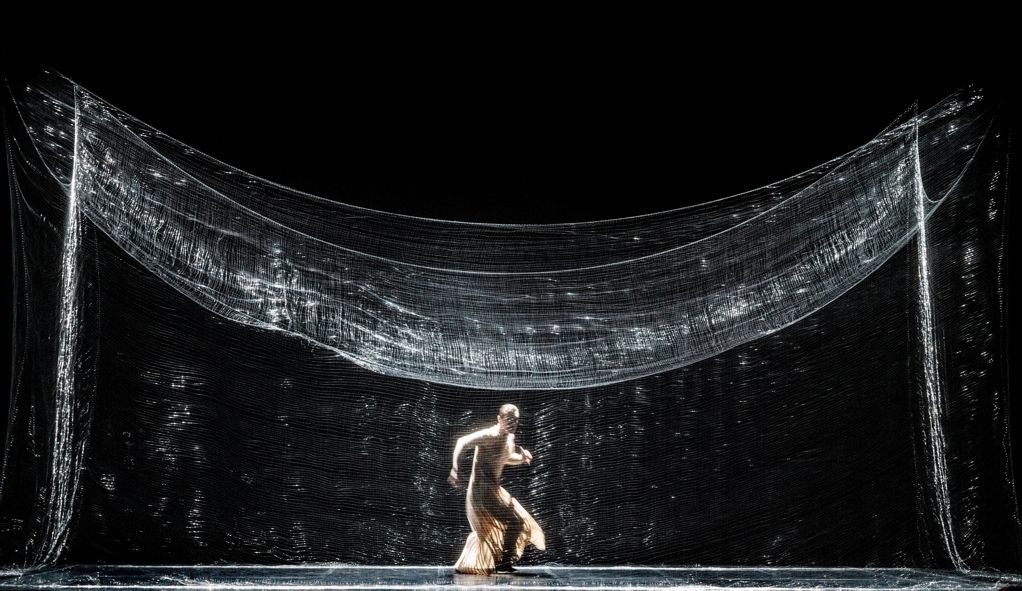

THE INSTALLATION: EGOFor this production artist Lonneke Gordijn (Studio DRIFT) developed the overwhelming installation Ego, a handwoven mobile sculpture made of nylon thread measuring 9 x 4.5 x 4.5 metres that fills almost the entire stage. Ego represents the perspective of man and shows how hope, truth and emotions are a direct result of either the rigidity or the dynamism of our thoughts.

Jointly with the interactions of singers and dancers, the sculpture takes us into Orpheus’ inner world. Orpheus is stuck in his own inflexible views about love and life. It is only when his world fully collapses – after he loses Euridice – that he rises above his own self. He has to face the laws of nature, and this new goal in his life completely changes his perspective, suddenly making him a strong figure.

Ego is steered by motors, algorithms and specially developed software. During the performances, Ego is also ‘conducted’ manually so it can react to the tempo of the music. The motions of the sculpture depict Orpheus’ emotions, fears and strength. Ego is therefore not only the stage decor but also a soloist in this production.

A HOMOGENEOUS GROUP ONSTAGEDirector Monique Wagemakers and choreographer Nanine Linning chose to present the ten singers and ten dancers as a homogeneous group, and together with the installation Ego as asingle organism on the stage. Everyone in this opera is part of Orpheus’ inner world. Ego is his universe.

The other characters as such are not always recognisable as separate roles. All the singers and dancers remain onstage during the entire performance. The work process reflects this, as they always rehearse in a single studio. In this way, the theatrical direction and the choreography organically flow into each other. The daily regime and rehearsals include strength training, exercises in energy awareness, the body’s architecture, spatial relationships with each other, carrying and lifting each other, relaxation and tension, breathing techniques for movement and singing, and forming one single body as a group.

Linning: ‘By having the singers and dancers work physically together every day, the rough edges disappear. This results in a really exciting work process in which the entire cast is invited to see, feel and listen outside the beaten path. The dance language for this opera is eloquent without being anecdotic. As an artist and choreographer, this opera challenges me to create theatrical dance that integrates the poetic texts and fantastic atmospheric music. The bodies of the singers and dancers tell with and without words about Orpheus’ quest in search of happiness.’ The production’s dancers are part of Linning’s own Dance Company Nanine Linning, based in Germany.

COSTUMESFashion designer Marlou Breuls further developed the concept in the costumes for the entire cast’s singers and dancers. She chose close-fitting, skin-coloured costumes made of gauze. PVC strips are integrated as lines into the costumes, following the bodies and movements of the singers and dancers. Each cast member wears a costume with a unique line pattern that tells a different story for each individual and produces different effects with the lighting and projections. For the scenes in the underworld, Breuls includes materials such as pleated jackets and skirts that accentuate the movements of the singers and dancers.

THE MUSICConductor Hernán Schvartzman sees L’Orfeo as a timeless opera, ‘It is wonderful to see how an opera that is 400 years old can still be a contemporary work in each time period. Our making of a contemporary version, with its daring artistic choices, fully fits with the intentionof Claudio Monteverdi. Further elaborating on the work of his predecessors of the Camerata Fiorentina in 1607, he even created an entire new art form: opera.’

‘In general, composers of Monteverdi’s time were not that accurate when notating instrumental scores. By contrast, Monteverdi goes into great detail in this opera, with a rich palette of colours and strong symbolic connotations: flutes for the shepherd, organ and harp symbolising Orpheus’ harp, and trombones and regals for the underworld.’ ‘I am very pleased with the collaboration with Baroque ensemble La Sfera Armoniosa; they are specialised in 17th-century music, and their musicians have played with the best ensembles around the world.’

THE COMPOSER AND HIS MUSICDuring his life, Monteverdi (1567-1643) was the greatest promoter of the brand-new genre of opera, and his musical fable L’Orfeo is the only work from that initial period that still manages to be both exciting and moving. The composer follows the tradition of his time by placing the music fully in service of the text, but what distinguishes him from his contemporaries is the outstanding inventiveness with which he does it. For the declamation of the text, Monteverdi comes up with countless different musical formulas that never sound contrived. There are no arias such as those we hear in operas of later generations. Even the highlight of the opera, the long monologue Possente spirto, in which Orpheus has to deploy all his musical talents in order to enter the underworld, can hardly be considered melodic to our ears: it sounds more like a beautifully ornamented recitativo. Monteverdi alternates these deep and virtuoso moments with lighter scenes in which he uses his most beautiful melodies for choral and dance music.

Interview mit Monique Wagenakers

Monteverdis „Uroper“ als zeitgenössisches Gesamtkunstwerk

„In uns allen steckt ein Orpheus“

Was Orpheus durchmacht, ist kein Trauerprozess laut den Machern von L'Orfeo. Regisseurin Monique Wagemakers: „Orpheus kann sich nicht von dem Schmerz der Vergangenheit lösen. Das hindert ihn daran, Glück zu erleben, wenn es da ist.“

Regisseurin Monique Wagenakers kommt gerade von einem Treffen mit dem Lichtdesigner und dem technischen Direktor von Nederlandse Reisopera (Niederländische Reiseoper). Diese außergewöhnliche Inszenierung von L'Orfeo (1607) erfordert viel Aufmerksamkeit. Die „Uroper“ von Monteverdi als zeitgenössisches Gesamtkunstwerk, mit Wagemakers, der Künstlerin Lonneke Gordijn vom Studio Drift und der Choreographin Nanine Linning als treibende Kraft. Gemeinsam entwickelten sie das Konzept. Später stieß noch die Modedesignerin Marlou Breuls hinzu. Jede einzelne von ihnen ist eine eigenständige Künstlerin mit internationalem Ruf. Ein intensiver Prozess, meint die Regisseurin, vor allem aber eine „wahnsinnig tolle“ Erfahrung.

Zwischen Leben und Tod

Das Designerduo Studio Drift verbindet Natur und Technik zu kuriosen Installationen. Lonneke Gordijn war vor allem mit Orpheus beschäftigt, denn während ihr Partner Ralph Nauta sich hauptsächlich auf die Technik konzentriert, widmet sie sich dem natürlichen Element. Monique Wagemakers: „Lonneke arbeitet mit ihren Installationen an der Grenze von Leben und Tod, von Tag und Nacht, von in Starre verharren und in Bewegung kommen. Genau das, worum es bei L‘Orfeo geht.“

Die Arbeit von Nanine Linning passt perfekt dazu. „Mich interessiert das Instinktive“, gab die Choreographin als den roten Faden in ihrem Werk an. Entgegen dem Schubladendenken kombiniert sie Tanz mit Design, Video, Technologie, bildender Kunst und Mode. Ihre Inszenierungen, wie Bacon und Khôra, werden für ihre Intensität gerühmt. „Sie hat eine deutliche, starke und sehr körperliche Tanzsprache, mit der sie wahnsinnig viel zum Ausdruck bringt“, sagt Wagemakers.

Dreamteam

Das ist das „Dream-Team“, das eine Antwort auf die grundlegende Frage der Regisseurin finden musste. Wie ist es möglich, dass der mythische Sänger Orpheus bereits jahrhundertelang unzählige Künstler inspiriert hat? Wagemakers: „Was bewegt all diese Komponisten, Dichter, Maler, Schriftsteller und andere so sehr, dass sie seine Geschichte immer wieder erzählen wollen? Obwohl es im Grunde genommen eine sehr bescheidene Erzählung ist. Ovid widmet ihr in seinen Metamorphosen kaum ein paar Seiten.“ Sie wusste, sie brauchte Künstler(innen), um eine Antwort auf diese Frage zu finden.

Für die Kostüme wurde die junge Modedesignerin Marlou Breuls gewonnen. Während man die Charaktere in der Regel leicht an ihrer Kleidung erkennen kann, ist der Unterschied hier weniger prägnant, erläutert Monique Wagemakers. „Zehn Sänger und zehn Tänzer bilden eine homogene Gruppe, einen Organismus. Zusammen sind sie sozusagen der eine Körper, aus dem die Geschichte erzählt wird.

Kunstwerk spiegelt Emotionen

Die Sänger und Tänzer stehen ständig auf der Bühne, auf der sie in unterschiedlichen Zusammenstellungen mal Teil des Organismus sind, mal in ihrer Umgebung aufgehen oder zu einer Figur werden. So wie die Eurydikes, die auch nach ihrem Tod Teil des Gesamten bleibt. So ungewöhnlich die Gestaltung auch sein mag, es bleibt eine Oper, versichert uns die Regisseurin. „Es ist kein experimentelles Theater. Sie werden sofort in Orpheus Welt entführt.“ Die bewegende und sich ständig verändernde Installation von Studio Drift zeigt die Emotionen des mythischen Künstlers, der mit seinem Gesang versucht, seine geliebte Eurydike aus der Unterwelt zu retten.

Was hat Wagemakers angetrieben, die x-te Macherin dieser Geschichte zu sein? „Natürlich habe ich mich auf das Wesentliche der Musik und des Librettos konzentriert. Was passiert da genau? Der Kern ist: Orpheus bleibt in der Vergangenheit stecken. Selbst wenn das Glück da ist, ist er nicht in der Lage, dieses Glück zu fühlen. Selbst an seinem Hochzeitstag erinnert er sich an die Zeit, da er unglücklich und allein war. Unterdessen pflückt Eurydike Blumen; sie wird von einer Schlange gebissen und stirbt. Und wenn das Böse erst einmal geschehen ist, weigert er sich, dies zu akzeptieren.“

Zeit zurückdrehen

Womit der Spiegel direkt vor unserer Nase hängt. Wagemakers: „Wir alle haben etwas von Orpheus in uns. In katastrophalen Momenten wollen wir nur eines und zwar die Zeit zurückdrehen. „Hätte ich nur, wenn ich nur ...“ Orpheus lässt Worten Taten folgen und holt seine Geliebte aus dem Schattenreich zurück. Aber er kann dabei nicht der Versuchung widerstehen, sie anzuschauen, woraufhin er sie dennoch für immer verliert. Warum schaut er zurück? Weil er mit dieser Richtung vertraut ist, ist darauf die einfache Antwort von Wagemakers. „In die Zukunft schauen, das hat er noch nie gemacht und das kann er auch nicht. Daher stammt auch seine Unsicherheit. Beim geringsten Anlass erschreckt er und blickt wieder zurück.“

Im Grunde spiegelt Monteverdis Musik auch den Übergang von Renaissance und Barock wider. Wagemakers: „Man hört, dass Orpheus noch in den alten Zeiten feststeckt, während sich die Zukunft sich bereits im Barock abspielt, wo es mehr Raum für Emotionen gibt.“ Für sie wird der fragmentarische Charakter der Musik eingehend durch ihre Tiefe kompensiert. „Die Musik berührt Sie in Ihrer Seele, ist sehr rein. Bei Striggios Libretto geht es auffallend häufig um „Das Glück“. Orpheus ist das Symbol für die Macht der Musik. Orpheus Suche, die alle immer wieder aufs Neue inspiriert... Die Musik lässt einen spüren, was er durchmacht und wie er damit umgeht. ”

Leben im Moment

Für Wagemakers und ihre Macherinnen-Kolleginnen ist klar: „Was Orpheus durchmacht, ist kein Trauerprozess.“ Für das Team geht es in dieser Oper viel mehr um die Unfähigkeit, im Moment zu leben und das Glück zu spüren, wenn es da ist. Und das gibt es zu allen Zeiten, obwohl es zu unseren Zeiten mehr oder weniger das ultimative Ziel ist. Es ist laut Wagemakers nach wie vor ziemlich

schwierig, sich das Leben zu greifen. „Nicht zu viel zurückschauen, sich nicht zu sehr auf die Zukunft konzentrieren. Glücklich sein im Moment.“

Sie verweist auf die Aussage Apollos gegenüber seinem Sohn Orpheus am Ende der Oper. „Warum hältst du weiter an deinen Ressentiments und deiner Trauer fest, weißt du denn nicht, dass irdisches Glück nie endlos lange andauert?“

Ingrid Bosman, 2019

---| Pressemeldung Nederlandse Reisopera |---